DNA stores our genetic code in an elegant double helix. But some argue that this elegance is overrated. “DNA as a molecule has many things wrong with it,” said Steven Benner, an organic chemist at the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Florida.

Nearly 30 years ago, Benner sketched out better versions of both DNA and its chemical cousin RNA, adding new letters and other additions that would expand their repertoire of chemical feats. He wondered why these improvements haven’t occurred in living creatures. Nature has written the entire language of life using just four chemical letters: G, C, A and T. Did our genetic code settle on these four nucleotides for a reason? Or was this system one of many possibilities, selected by simple chance? Perhaps expanding the code could make it better.

Benner’s early attempts at synthesizing new chemical letters failed. But with each false start, his team learned more about what makes a good nucleotide and gained a better understanding of the precise molecular details that make DNA and RNA work. The researchers’ efforts progressed slowly, as they had to design new tools to manipulate the extended alphabet they were building. “We have had to re-create, for our artificially designed DNA, all of the molecular biology that evolution took 4 billion years to create for natural DNA,” Benner said.

Now, after decades of work, Benner’s team has synthesized artificially enhanced DNA that functions much like ordinary DNA, if not better. In two papers published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society last month, the researchers have shown that two synthetic nucleotides called P and Z fit seamlessly into DNA’s helical structure, maintaining the natural shape of DNA. Moreover, DNA sequences incorporating these letters can evolve just like traditional DNA, a first for an expanded genetic alphabet.

The new nucleotides even outperform their natural counterparts. When challenged to evolve a segment that selectively binds to cancer cells, DNA sequences using P and Z did better than those without.

“When you compare the four-nucleotide and six-nucleotide alphabet, the six-nucleotide version seems to have won out,” said Andrew Ellington, a biochemist at the University of Texas, Austin, who was not involved in the study.

Benner has lofty goals for his synthetic molecules. He wants to create an alternative genetic system in which proteins — intricately folded molecules that perform essential biological functions — are unnecessary. Perhaps, Benner proposes, instead of our standard three-component system of DNA, RNA and proteins, life on other planets evolved with just two.

Better Blueprints for Life

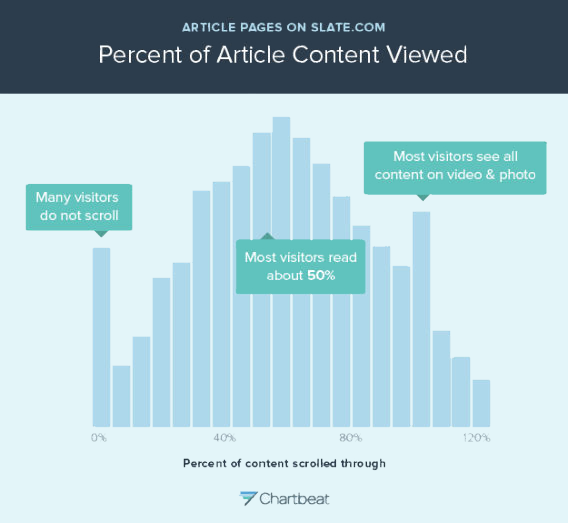

The primary job of DNA is to store information. Its sequence of letters contains the blueprints for building proteins. Our current four-letter alphabet encodes 20 amino acids, which are strung together to create millions of different proteins. But a six-letter alphabet could encode as many as 216 possible amino acids and many, many more possible proteins.

Expanding the genetic alphabet dramatically expands the number of possible amino acids and proteins that cells can build, at least in theory. The existing four-letter alphabet produces 20 amino acids (small circle) while a six-letter alphabet could produce 216 possible amino acids (large circle).

Why nature stuck with four letters is one of biology’s fundamental questions. Computers, after all, use a binary system with just two “letters” — 0s and 1s. Yet two letters probably aren’t enough to create the array of biological molecules that make up life. “If you have a two-letter code, you limit the number of combinations you get,” said Ramanarayanan Krishnamurthy, a chemist at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

On the other hand, additional letters could make the system more error prone. DNA bases come in pairs — G pairs with C and A pairs with T. It’s this pairing that endows DNA with the ability to pass along genetic information. With a larger alphabet, each letter has a greater chance of pairing with the wrong partner, and new copies of DNA might harbor more mistakes. “If you go past four, it becomes too unwieldy,” Krishnamurthy said.

But perhaps the advantages of a larger alphabet can outweigh the potential drawbacks. Six-letter DNA could densely pack in genetic information. And perhaps six-letter RNA could take over some of the jobs now handled by proteins, which perform most of the work in the cell.

Proteins have a much more flexible structure than DNA and RNA and are capable of folding into an array of complex shapes. A properly folded protein can act as a molecular lock, opening a chamber only for the right key. Or it can act as a catalyst, capturing and bringing together different molecules for chemical reactions.

Adding new letters to RNA could give it some of these abilities. “Six letters can potentially fold into more, different structures than four letters,” Ellington said.

Back when Benner was sketching out ideas for alternative DNA and RNA, it was this potential that he had in mind. According to the most widely held theory of life’s origins, RNA once performed both the information-storage job of DNA and the catalytic job of proteins. Benner realized that there are many ways to make RNA a better catalyst.

“With just these little insights, I was able to write down the structures that are in my notebook as alternatives that would make DNA and RNA better,” Benner said. “So the question is: Why did life not make these alternatives? One way to find out was to make them ourselves, in the laboratory, and see how they work.”

Steven Benner’s lab notebook from 1985 outlining plans to synthesize “better” DNA and RNA by adding new chemical letters.

It’s one thing to design new codes on paper, and quite another to make them work in real biological systems. Other researchers have created their own additions to the genetic code, in one case even incorporating new letters into living bacteria. But these other bases fit together a bit differently from natural ones, stacking on top of each other rather than linking side by side. This can distort the shape of DNA, particularly when a number of these bases cluster together. Benner’s P-Z pair, however, is designed to mimic natural bases.

One of the new papers by Benner’s team shows that Z and P are yoked together by the same chemical bond that ties A to T and C to G. (This bond is known as Watson-Crick pairing, after the scientists who discovered DNA’s structure.) Millie Georgiadis, a chemist at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, along with Benner and other collaborators, showed that DNA strands that incorporate Z and P retain their proper helical shape if the new letters are strung together or interspersed with natural letters.

“This is very impressive work,” said Jack Szostak, a chemist at Harvard University who studies the origin of life, and who was not involved in the study. “Finding a novel base pair that does not grossly disrupt the double-helical structure of DNA has been quite difficult.”

The team’s second paper demonstrates how well the expanded alphabet works. Researchers started with a random library of DNA strands constructed from the expanded alphabet and then selected the strands that were able to bind to liver cancer cells but not to other cells. Of the 12 successful binders, the best had Zs and Ps in their sequences, while the weakest did not.

“More functionality in the nucleobases has led to greater functionality in nucleic acids themselves,” Ellington said. In other words, the new additions appear to improve the alphabet, at least under these conditions.

Steven Benner, an organic chemist at the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Florida, is expanding the genetic alphabet.

But additional experiments are needed to determine how broadly that’s true. “I think it will take more work, and more direct comparisons, to be sure that a six-letter version generally results in ‘better’ aptamers [short DNA strands] than four-letter DNA,” Szostak said. For example, it’s unclear whether the six-letter alphabet triumphed because it provided more sequence options or because one of the new letters is simply better at binding, Szostak said.

Benner wants to expand his genetic alphabet even further, which could enhance its functional repertoire. He’s working on creating a 10- or 12-letter system and plans to move the new alphabet into living cells. Benner’s and others’ synthetic molecules have already proved useful in medical and biotech applications, such as diagnostic tests for HIV and other diseases. Indeed, Benner’s work helped to found the burgeoning field of synthetic biology, which seeks to build new life, in addition to forming useful tools from molecular parts.

Why Life’s Code Is Limited

Benner’s work and that of other researchers suggests that a larger alphabet has the capacity to enhance DNA’s function. So why didn’t nature expand its alphabet in the 4 billion years it has had to work on it? It could be because a larger repertoire has potential disadvantages. Some of the structures made possible by a larger alphabet might be of poor quality, with a greater risk of misfolding, Ellington said.

Nature was also effectively locked into the system at hand when life began. “Once [nature] has made a decision about which molecular structures to place at the core of its molecular biology, it has relatively little opportunity to change those decisions,” Benner said. “By constructing unnatural systems, we are learning not only about the constraints at the time that life first emerged, but also about constraints that prevent life from searching broadly within the imagination of chemistry.”

The genetic code — made up of the four letters, A, T, G and C — stores the blueprint for proteins. DNA is first transcribed into RNA and then translated into proteins, which fold into specific shapes.

Benner aims to make a thorough search of that chemical space, using his discoveries to make new and improved versions of both DNA and RNA. He wants to make DNA better at storing information and RNA better at catalyzing reactions. He hasn’t shown directly that the P-Z base pairs do that. But both bases have the potential to help RNA fold into more complex structures, which in turn could make proteins better catalysts. P has a place to add a “functional group,” a molecular structure that helps folding and is typically found in proteins. And Z has a nitro group, which could aid in molecular binding.

In modern cells, RNA acts as an intermediary between DNA and proteins. But Benner ultimately hopes to show that the three-biopolymer system — DNA, RNA and proteins — that exists throughout life on Earth isn’t essential. With better-engineered DNA and RNA, he says, perhaps proteins are unnecessary.

Indeed, the three-biopolymer system may have drawbacks, since information flows only one way, from DNA to RNA to proteins. If a DNA mutation produces a more efficient protein, that mutation will spread slowly, as organisms without it eventually die off.

What if the more efficient protein could spread some other way, by directly creating new DNA? DNA and RNA can transmit information in both directions. So a helpful RNA mutation could theoretically be transformed into beneficial DNA. Adaptations could thus lead directly to changes in the genetic code.

Benner predicts that a two-biopolymer system would evolve faster than our own three-biopolymer system. If so, this could have implications for life on distant planets. “If we find life elsewhere,” he said, “it would likely have the two-biopolymer system.”