Andrew Hickey

Shared posts

#1252; In which War is waged

The No-Cloning Theorem and the Human Condition: My After-Dinner Talk at QCRYPT

The following are the after-dinner remarks that I delivered at QCRYPT’2016, the premier quantum cryptography conference, on Thursday Sep. 15 in Washington DC. You could compare to my after-dinner remarks at QIP’2006 to see how much I’ve “”matured”” since then. Thanks so much to Yi-Kai Liu and the other organizers for inviting me and for putting on a really fantastic conference.

It’s wonderful to be here at QCRYPT among so many friends—this is the first significant conference I’ve attended since I moved from MIT to Texas. I do, however, need to register a complaint with the organizers, which is: why wasn’t I allowed to bring my concealed firearm to the conference? You know, down in Texas, we don’t look too kindly on you academic elitists in Washington DC telling us what to do, who we can and can’t shoot and so forth. Don’t mess with Texas! As you might’ve heard, many of us Texans even support a big, beautiful, physical wall being built along our border with Mexico. Personally, though, I don’t think the wall proposal goes far enough. Forget about illegal immigration and smuggling: I don’t even want Americans and Mexicans to be able to win the CHSH game with probability exceeding 3/4. Do any of you know what kind of wall could prevent that? Maybe a metaphysical wall.

OK, but that’s not what I wanted to talk about. When Yi-Kai asked me to give an after-dinner talk, I wasn’t sure whether to try to say something actually relevant to quantum cryptography or just make jokes. So I’ll do something in between: I’ll tell you about research directions in quantum cryptography that are also jokes.

The subject of this talk is a deep theorem that stands as one of the crowning achievements of our field. I refer, of course, to the No-Cloning Theorem. Almost everything we’re talking about at this conference, from QKD onwards, is based in some way on quantum states being unclonable. If you read Stephen Wiesner’s paper from 1968, which founded quantum cryptography, the No-Cloning Theorem already played a central role—although Wiesner didn’t call it that. By the way, here’s my #1 piece of research advice to the students in the audience: if you want to become immortal, just find some fact that everyone already knows and give it a name!

I’d like to pose the question: why should our universe be governed by physical laws that make the No-Cloning Theorem true? I mean, it’s possible that there’s some other reason for our universe to be quantum-mechanical, and No-Cloning is just a byproduct of that. No-Cloning would then be like the armpit of quantum mechanics: not there because it does anything useful, but just because there’s gotta be something under your arms.

OK, but No-Cloning feels really fundamental. One of my early memories is when I was 5 years old or so, and utterly transfixed by my dad’s home fax machine, one of those crappy 1980s fax machines with wax paper. I kept thinking about it: is it really true that a piece of paper gets transmaterialized, sent through a wire, and reconstituted at the other location? Could I have been that wrong about how the universe works? Until finally I got it—and once you get it, it’s hard even to recapture your original confusion, because it becomes so obvious that the world is made not of stuff but of copyable bits of information. “Information wants to be free!”

The No-Cloning Theorem represents nothing less than a partial return to the view of the world that I had before I was five. It says that quantum information doesn’t want to be free: it wants to be private. There is, it turns out, a kind of information that’s tied to a particular place, or set of places. It can be moved around, or even teleported, but it can’t be copied the way a fax machine copies bits.

So I think it’s worth at least entertaining the possibility that we don’t have No-Cloning because of quantum mechanics; we have quantum mechanics because of No-Cloning—or because quantum mechanics is the simplest, most elegant theory that has unclonability as a core principle. But if so, that just pushes the question back to: why should unclonability be a core principle of physics?

Quantum Key Distribution

A first suggestion about this question came from Gilles Brassard, who’s here. Years ago, I attended a talk by Gilles in which he speculated that the laws of quantum mechanics are what they are because Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) has to be possible, while bit commitment has to be impossible. If true, that would be awesome for the people at this conference. It would mean that, far from being this exotic competitor to RSA and Diffie-Hellman that’s distance-limited and bandwidth-limited and has a tiny market share right now, QKD would be the entire reason why the universe is as it is! Or maybe what this really amounts to is an appeal to the Anthropic Principle. Like, if QKD hadn’t been possible, then we wouldn’t be here at QCRYPT to talk about it.

Quantum Money

But maybe we should search more broadly for the reasons why our laws of physics satisfy a No-Cloning Theorem. Wiesner’s paper sort of hinted at QKD, but the main thing it had was a scheme for unforgeable quantum money. This is one of the most direct uses imaginable for the No-Cloning Theorem: to store economic value in something that it’s physically impossible to copy. So maybe that’s the reason for No-Cloning: because God wanted us to have e-commerce, and didn’t want us to have to bother with blockchains (and certainly not with credit card numbers).

The central difficulty with quantum money is: how do you authenticate a bill as genuine? (OK, fine, there’s also the dificulty of how to keep a bill coherent in your wallet for more than a microsecond or whatever. But we’ll leave that for the engineers.)

In Wiesner’s original scheme, he solved the authentication problem by saying that, whenever you want to verify a quantum bill, you bring it back to the bank that printed it. The bank then looks up the bill’s classical serial number in a giant database, which tells the bank in which basis to measure each of the bill’s qubits.

With this system, you can actually get information-theoretic security against counterfeiting. OK, but the fact that you have to bring a bill to the bank to be verified negates much of the advantage of quantum money in the first place. If you’re going to keep involving a bank, then why not just use a credit card?

That’s why over the past decade, some of us have been working on public-key quantum money: that is, quantum money that anyone can verify. For this kind of quantum money, it’s easy to see that the No-Cloning Theorem is no longer enough: you also need some cryptographic assumption. But OK, we can consider that. In recent years, we’ve achieved glory by proposing a huge variety of public-key quantum money schemes—and we’ve achieved even greater glory by breaking almost all of them!

After a while, there were basically two schemes left standing: one based on knot theory by Ed Farhi, Peter Shor, et al. That one has been proven to be secure under the assumption that it can’t be broken. The second scheme, which Paul Christiano and I proposed in 2012, is based on hidden subspaces encoded by multivariate polynomials. For our scheme, Paul and I were able to do better than Farhi et al.: we gave a security reduction. That is, we proved that our quantum money scheme is secure, unless there’s a polynomial-time quantum algorithm to find hidden subspaces encoded by low-degree multivariate polynomials (yadda yadda, you can look up the details) with much greater success probability than we thought possible.

Today, the situation is that my and Paul’s security proof remains completely valid, but meanwhile, our money is completely insecure! Our reduction means the opposite of what we thought it did. There is a break of our quantum money scheme, and as a consequence, there’s also a quantum algorithm to find large subspaces hidden by low-degree polynomials with much better success probability than we’d thought. What happened was that first, some French algebraic cryptanalysts—Faugere, Pena, I can’t pronounce their names—used Gröbner bases to break the noiseless version of scheme, in classical polynomial time. So I thought, phew! At least I had acceded when Paul insisted that we also include a noisy version of the scheme. But later, Paul noticed that there’s a quantum reduction from the problem of breaking our noisy scheme to the problem of breaking the noiseless one, so the former is broken as well.

I’m choosing to spin this positively: “we used quantum money to discover a striking new quantum algorithm for finding subspaces hidden by low-degree polynomials. Err, yes, that’s exactly what we did.”

But, bottom line, until we manage to invent a better public-key quantum money scheme, or otherwise sort this out, I don’t think we’re entitled to claim that God put unclonability into our universe in order for quantum money to be possible.

Copy-Protected Quantum Software

So if not money, then what about its cousin, copy-protected software—could that be why No-Cloning holds? By copy-protected quantum software, I just mean a quantum state that, if you feed it into your quantum computer, lets you evaluate some Boolean function on any input of your choice, but that doesn’t let you efficiently prepare more states that let the same function be evaluated. I think this is important as one of the preeminent evil applications of quantum information. Why should nuclear physicists and genetic engineers get a monopoly on the evil stuff?

OK, but is copy-protected quantum software even possible? The first worry you might have is that, yeah, maybe it’s possible, but then every time you wanted to run the quantum program, you’d have to make a measurement that destroyed it. So then you’d have to go back and buy a new copy of the program for the next run, and so on. Of course, to the software company, this would presumably be a feature rather than a bug!

But as it turns out, there’s a fact many of you know—sometimes called the “Gentle Measurement Lemma,” other times the “Almost As Good As New Lemma”—which says that, as long as the outcome of your measurement on a quantum state could be predicted almost with certainty given knowledge of the state, the measurement can be implemented in such a way that it hardly damages the state at all. This tells us that, if quantum money, copy-protected quantum software, and the other things we’re talking about are possible at all, then they can also be made reusable. I summarize the principle as: “if rockets, then space shuttles.”

Much like with quantum money, one can show that, relative to a suitable oracle, it’s possible to quantumly copy-protect any efficiently computable function—or rather, any function that’s hard to learn from its input/output behavior. Indeed, the implementation can be not only copy-protected but also obfuscated, so that the user learns nothing besides the input/output behavior. As Bill Fefferman pointed out in his talk this morning, the No-Cloning Theorem lets us bypass Barak et al.’s famous result on the impossibility of obfuscation, because their impossibility proof assumed the ability to copy the obfuscated program.

Of course, what we really care about is whether quantum copy-protection is possible in the real world, with no oracle. I was able to give candidate implementations of quantum copy-protection for extremely special functions, like one that just checks the validity of a password. In the general case—that is, for arbitrary programs—Paul Christiano has a beautiful proposal for how to do it, which builds on our hidden-subspace money scheme. Unfortunately, since our money scheme is currently in the shop being repaired, it’s probably premature to think about the security of the much more complicated copy-protection scheme! But these are wonderful open problems, and I encourage any of you to come and scoop us. Once we know whether uncopyable quantum software is possible at all, we could then debate whether it’s the “reason” for our universe to have unclonability as a core principle.

Unclonable Proofs and Advice

Along the same lines, I can’t resist mentioning some favorite research directions, which some enterprising student here could totally turn into a talk at next year’s QCRYPT.

Firstly, what can we say about clonable versus unclonable quantum proofs—that is, QMA witness states? In other words: for which problems in QMA can we ensure that there’s an accepting witness that lets you efficiently create as many additional accepting witnesses as you want? (I mean, besides the QCMA problems, the ones that have short classical witnesses?) For which problems in QMA can we ensure that there’s an accepting witness that doesn’t let you efficiently create any additional accepting witnesses? I do have a few observations about these questions—ask me if you’re interested—but on the whole, I believe almost anything one can ask about them remains open.

Admittedly, it’s not clear how much use an unclonable proof would be. Like, imagine a quantum state that encoded a proof of the Riemann Hypothesis, and which you would keep in your bedroom, in a glass orb on your nightstand or something. And whenever you felt your doubts about the Riemann Hypothesis resurfacing, you’d take the state out of its orb and measure it again to reassure yourself of RH’s truth. You’d be like, “my preciousssss!” And no one else could copy your state and thereby gain the same Riemann-faith-restoring powers that you had. I dunno, I probably won’t hawk this application in a DARPA grant.

Similarly, one can ask about clonable versus unclonable quantum advice states—that is, initial states that are given to you to boost your computational power beyond that of an ordinary quantum computer. And that’s also a fascinating open problem.

OK, but maybe none of this quite gets at why our universe has unclonability. And this is an after-dinner talk, so do you want me to get to the really crazy stuff? Yes?

Self-Referential Paradoxes

OK! What if unclonability is our universe’s way around the paradoxes of self-reference, like the unsolvability of the halting problem and Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem? Allow me to explain what I mean.

In kindergarten or wherever, we all learn Turing’s proof that there’s no computer program to solve the halting problem. But what isn’t usually stressed is that that proof actually does more than advertised. If someone hands you a program that they claim solves the halting problem, Turing doesn’t merely tell you that that person is wrong—rather, he shows you exactly how to expose the person as a jackass, by constructing an example input on which their program fails. All you do is, you take their claimed halt-decider, modify it in some simple way, and then feed the result back to the halt-decider as input. You thereby create a situation where, if your program halts given its own code as input, then it must run forever, and if it runs forever then it halts. “WHOOOOSH!” [head-exploding gesture]

OK, but now imagine that the program someone hands you, which they claim solves the halting problem, is a quantum program. That is, it’s a quantum state, which you measure in some basis depending on the program you’re interested in, in order to decide whether that program halts. Well, the truth is, this quantum program still can’t work to solve the halting problem. After all, there’s some classical program that simulates the quantum one, albeit less efficiently, and we already know that the classical program can’t work.

But now consider the question: how would you actually produce an example input on which this quantum program failed to solve the halting problem? Like, suppose the program worked on every input you tried. Then ultimately, to produce a counterexample, you might need to follow Turing’s proof and make a copy of the claimed quantum halt-decider. But then, of course, you’d run up against the No-Cloning Theorem!

So we seem to arrive at the conclusion that, while of course there’s no quantum program to solve the halting problem, there might be a quantum program for which no one could explicitly refute that it solved the halting problem, by giving a counterexample.

I was pretty excited about this observation for a day or two, until I noticed the following. Let’s suppose your quantum program that allegedly solves the halting problem has n qubits. Then it’s possible to prove that the program can’t possibly be used to compute more than, say, 2n bits of Chaitin’s constant Ω, which is the probability that a random program halts. OK, but if we had an actual oracle for the halting problem, we could use it to compute as many bits of Ω as we wanted. So, suppose I treated my quantum program as if it were an oracle for the halting problem, and I used it to compute the first 2n bits of Ω. Then I would know that, assuming the truth of quantum mechanics, the program must have made a mistake somewhere. There would still be something weird, which is that I wouldn’t know on which input my program had made an error—I would just know that it must’ve erred somewhere! With a bit of cleverness, one can narrow things down to two inputs, such that the quantum halt-decider must have erred on at least one of them. But I don’t know whether it’s possible to go further, and concentrate the wrongness on a single query.

We can play a similar game with other famous applications of self-reference. For example, suppose we use a quantum state to encode a system of axioms. Then that system of axioms will still be subject to Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem (which I guess I believe despite the umlaut). If it’s consistent, it won’t be able to prove all the true statements of arithmetic. But we might never be able to produce an explicit example of a true statement that the axioms don’t prove. To do so we’d have to clone the state encoding the axioms and thereby violate No-Cloning.

Personal Identity

But since I’m a bit drunk, I should confess that all this stuff about Gödel and self-reference is just a warmup to what I really wanted to talk about, which is whether the No-Cloning Theorem might have anything to do with the mysteries of personal identity and “free will.” I first encountered this idea in Roger Penrose’s book, The Emperor’s New Mind. But I want to stress that I’m not talking here about the possibility that the brain is a quantum computer—much less about the possibility that it’s a quantum-gravitational hypercomputer that uses microtubules to solve the halting problem! I might be drunk, but I’m not that drunk. I also think that the Penrose-Lucas argument, based on Gödel’s Theorem, for why the brain has to work that way is fundamentally flawed.

But here I’m talking about something different. See, I have a lot of friends in the Singularity / Friendly AI movement. And I talk to them whenever I pass through the Bay Area, which is where they congregate. And many of them express great confidence that before too long—maybe in 20 or 30 years, maybe in 100 years—we’ll be able to upload ourselves to computers and live forever on the Internet (as opposed to just living 70% of our lives on the Internet, like we do today).

This would have lots of advantages. For example, any time you were about to do something dangerous, you’d just make a backup copy of yourself first. If you were struggling with a conference deadline, you’d spawn 100 temporary copies of yourself. If you wanted to visit Mars or Jupiter, you’d just email yourself there. If Trump became president, you’d not run yourself for 8 years (or maybe 80 or 800 years). And so on.

Admittedly, some awkward questions arise. For example, let’s say the hardware runs three copies of your code and takes a majority vote, just for error-correcting purposes. Does that bring three copies of you into existence, or only one copy? Or let’s say your code is run homomorphically encrypted, with the only decryption key stored in another galaxy. Does that count? Or you email yourself to Mars. If you want to make sure that you’ll wake up on Mars, is it important that you delete the copy of your code that remains on earth? Does it matter whether anyone runs the code or not? And what exactly counts as “running” it? Or my favorite one: could someone threaten you by saying, “look, I have a copy of your code, and if you don’t do what I say, I’m going to make a thousand copies of it and subject them all to horrible tortures?”

The issue, in all these cases, is that in a world where there could be millions of copies of your code running on different substrates in different locations—or things where it’s not even clear whether they count as a copy or not—we don’t have a principled way to take as input a description of the state of the universe, and then identify where in the universe you are—or even a probability distribution over places where you could be. And yet you seem to need such a way in order to make predictions and decisions.

A few years ago, I wrote this gigantic, post-tenure essay called The Ghost in the Quantum Turing Machine, where I tried to make the point that we don’t know at what level of granularity a brain would need to be simulated in order to duplicate someone’s subjective identity. Maybe you’d only need to go down to the level of neurons and synapses. But if you needed to go all the way down to the molecular level, then the No-Cloning Theorem would immediately throw a wrench into most of the paradoxes of personal identity that we discussed earlier.

For it would mean that there were some microscopic yet essential details about each of us that were fundamentally uncopyable, localized to a particular part of space. We would all, in effect, be quantumly copy-protected software. Each of us would have a core of unpredictability—not merely probabilistic unpredictability, like that of a quantum random number generator, but genuine unpredictability—that an external model of us would fail to capture completely. Of course, by having futuristic nanorobots scan our brains and so forth, it would be possible in principle to make extremely realistic copies of us. But those copies necessarily wouldn’t capture quite everything. And, one can speculate, maybe not enough for your subjective experience to “transfer over.”

Maybe the most striking aspect of this picture is that sure, you could teleport yourself to Mars—but to do so you’d need to use quantum teleportation, and as we all know, quantum teleportation necessarily destroys the original copy of the teleported state. So we’d avert this metaphysical crisis about what to do with the copy that remained on Earth.

Look—I don’t know if any of you are like me, and have ever gotten depressed by reflecting that all of your life experiences, all your joys and sorrows and loves and losses, every itch and flick of your finger, could in principle be encoded by a huge but finite string of bits, and therefore by a single positive integer. (Really? No one else gets depressed about that?) It’s kind of like: given that this integer has existed since before there was a universe, and will continue to exist after the universe has degenerated into a thin gruel of radiation, what’s the point of even going through the motions? You know?

But the No-Cloning Theorem raises the possibility that at least this integer is really your integer. At least it’s something that no one else knows, and no one else could know in principle, even with futuristic brain-scanning technology: you’ll always be able to surprise the world with a new digit. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but if it were true, then it seems like the sort of thing that would be worthy of elevating unclonability to a fundamental principle of the universe.

So as you enjoy your dinner and dessert at this historic Mayflower Hotel, I ask you to reflect on the following. People can photograph this event, they can video it, they can type up transcripts, in principle they could even record everything that happens down to the millimeter level, and post it on the Internet for posterity. But they’re not gonna get the quantum states. There’s something about this evening, like about every evening, that will vanish forever, so please savor it while it lasts. Thank you.

Update (Sep. 20): Unbeknownst to me, Marc Kaplan did video the event and put it up on YouTube! Click here to watch. Thanks very much to Marc! I hope you enjoy, even though of course, the video can’t precisely clone the experience of having been there.

[Note: The part where I raise my middle finger is an inside joke—one of the speakers during the technical sessions inadvertently did the same while making a point, causing great mirth in the audience.]

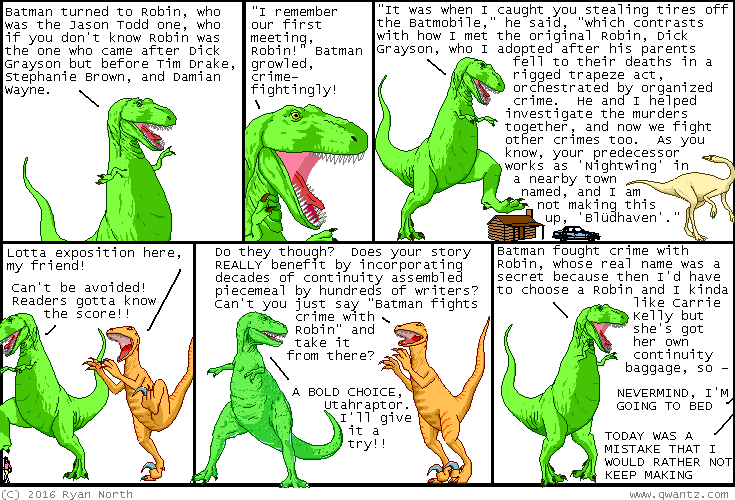

why does our town named "blüdhaven" have so much violent crime compared to "peacetopia", a nearby town of comparable population, it is a mystery

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | September 21st, 2016 | next | |

|

September 21st, 2016: I hope you enjoyed this comic about fictional character "Batman" who I must legally tell you is NOT owned by DC (Dinosaur Comics). – Ryan | |||

Business Musings: Good Things

While I was digging deep into the ugliness that traditional publishing contracts have devolved into, the indie publishing world has grown and changed and become even more positive. More than a light at the end of the tunnel, the indie world has become a haven to those of us willing to work hard and to understand that real achievement takes time.

It amazes me how far we have come in the publishing industry since the Kindle revolutionized the ebook in 2009. While indie publishing hasn’t exactly stabilized yet, it has become both easier and harder in the past few years.

Easier, because there are a lot more tools, and there’s more data that shows what works and what doesn’t. Harder, because so many fad-chasers who got rich quick off their fad have left in discouragement as their fad-based income decreased.

Here’s the truth of indie publishing, folks: It’s a business. It takes five to ten years for a business to become solid. So if you started your indie publishing business in 2010, you might (if you managed it well) be seeing some predictable patterns and very real growth. If you started last year, you’re still in the early years yet, and you have some tough times ahead.

Those of you new to this blog will note that I say “indie publishing” when so many others say “self-publishing.” The reason is simple: it now takes several people to produce a book. Yes, you can do most of it yourself (self-publishing) but to do it well, you need copy editors and maybe a cover designer, beta readers and some classes in marketing (or someone to teach you how to write ad copy). There are a lot of things worth hiring out, and some things you should keep close at hand, and those things all vary according to the author.

But very few authors go it 100% alone. Those authors are self-publishing. The rest of us, those who hire out a few (or all) of the jobs? We’re indie publishers.

So what has changed while I climbed into the muck and stared horrid contracts in the face?

A lot, much of which I did not make note of. I had to ask Allyson Longueira, publisher of WMG Publishing, for her list because I know she has one. Mostly, it’s a “we’ll get to that when we get to it” list, but it’s more organized than my “oh, cool!” list.

Thank you, Allyson! I couldn’t have written this blog post without you.

Top on her list of changes this year are innovations by Draft 2 Digital. A few years ago, D2D was the upstart rival of Smashwords, a way to publish ebooks DRM-free and to get them to hard-to-reach platforms overseas (or in some cases, in the U.S.—places like iBooks).

Nowadays, Smashwords looks like a twenty-year-old website, and creaks like one too. D2D is constantly improving, constantly innovating, and constantly adding new things. And, a plus for those who use D2D to disseminate their ebooks worldwide, D2D pays monthly. Smashwords pays quarterly. I hate that Smashwords sits on the money that long, and have slowly migrated a lot of product out of Smashwords because of the money and the creaky website and a whole bunch of other reasons.

Also, D2D gives writers a lot of incentive to go there. One incentive that you might have noticed on my blog in the last few weeks?

D2D has started something on its Books 2 Read site that D2D calls “universal links.” D2D calls it “one link for every reader everywhere.” And while it doesn’t quite cover everywhere, it does take the time out of list linking.

Frankly, I gave up listing all of the places my ebooks were available two years ago. It took me 20 minutes on every post to list all the links. I finally decided the readers could figure out where the book was on their own. I didn’t like that solution, but it was better than wasting countless hours over the year copying and pasting links.

D2D now lists all the ebook links it can find on one page for your book. An indie friend of mine refuses to use this service because it takes the reader off his website to another landing page, but I don’t mind that at all. (I also know how to click that little place on my WordPress site that says, “open link in new window.” <vbg>)

As a reader, I love having all the choices in one spot. I’ve used that option on other websites for traditionally published books. As a writer, I love the time savings.

And did I mention this service is free? Plus, D2D links to your affiliate accounts if you input them into the D2D system.

They call this Books 2 Read, which I’m just fine with. Books 2 Read provides another service for readers. It notifies them when their favorite authors release new titles.

Amazon does that—which I love, because that way, my regular readers often find my books before I announce them. Now, D2D has made that easier as well.

So has BookBub, which we will get to in a moment.

But let me finish with D2D. D2D provides free ebook conversion from Word documents. I hear that the conversion is a very good one. So if converting from word to ebook has been one of the daunting steps in your process, here’s a solution for you.

Now, BookBub. Just like Amazon and D2D, BookBub will notify your followers on their site of any new releases you have—even if those new releases are not part of a BookBub ad.

For those of you who don’t know, BookBub is a highly successful newsletter advertising service that informs readers who sign up and personalize their account of discounted ebooks in their areas of interest. The slots in the newsletter are paid, but BookBub advertising is effective.

For example, the daily email newsletter that goes out to crime fiction readers has (at the time of this writing) 3.8 million subscribers. If you advertise a free crime novel through that newsletter, BookBub will charge you $500 and estimate that you’ll get about 60,000 downloads. I personally don’t believe in paying something to give something away, so when I do a BookBub ad, I sell the books at a discount.

It costs anywhere from $1000 to $2500 to place a BookBub crime fiction ad for a discounted book, depending on the discount (the lower the book’s price, the cheaper the ad price). In these cases, BookBub says that the average number of books sold in this category will be about 4,000.

I’ve found that BookBub’s sales averages are on the low side. And, let me point out that every BookBub ad I’ve placed has made me a profit—because I do not pay to advertise my book for free. So if I discounted my crime novel to $2.99, it would cost me $2500 to advertise that discounted book on BookBub. At that price, I would make roughly $2.25 per book sold. And if BookBub’s averages are correct (and they usually are), I would make a gross profit of $9000. Subtract the cost of the ad, and I would net $6500.

This is why every indie author competes for the limited BookBub advertising slots. And these indie authors are competing with some traditional publishing houses now, as well.

If you run an ad campaign on BookBub, then they will collect followers for you and your titles. And once BookBub does that, they will advertise, for free, your newly released works.

We’ve talked for years about discoverability here. I’ve just told you three ways that are pretty hands-off to get your books discovered: Amazon does it for you automatically (for free); Books 2 Read will do it for you for free if you but sign up; and BookBub will do it once you’ve advertised with them.

It’s all about informing readers, folks.

Other places do this as well in a variety of ways, most of which I’m unfamiliar with. Goodreads does, for example, but I’ve been too busy to investigate it closely.

As I mentioned last week, the most precious commodity an indie writer has is time. There just isn’t enough of it, and no real way to do everything well. I’m writing this through bleary eyes, as I also prep for a week-long writers workshop. (If I don’t respond quickly to emails or comments this week, the workshop is why.) I’ve actually doubled my workload this week to compensate for losing next week—and what’s suffering is my hours of sleep.

Indies know what I’m talking about. So when services like D2D’s ebook conversion service comes along or the Books 2 Read universal links develop, they manage to do the one thing indies need the most: they save time.

We’ve investigated a couple of other time-savers, but haven’t used them yet. For example, if you want to give away free copies of a short story to your newsletter, you can upload all the files on your favorite newsletter service or make a private page on your website. Some plug-ins, like Enhanced Media Library, will make uploading the files on WordPress sites easier.

Or you can use BookFunnel. BookFunnel charges for the service (again, paying for free), but the costs appear to be minimal, and sometimes paying $20 annually is well worth it for the time that you save by not doing the thing yourself. Again, I haven’t tried this one, but I plan to at some point Real Soon Now.

Another service that caught my eye during this contracts-writing period was an audio distribution company that promised to distribute audiobooks all over the world through a variety of services. I waited long enough on this one to decide not to recommend right now. Initially, I wanted to use it, but the distribution agreement is onerous. A friend is trying to negotiate it right now, and if he’s successful, you’ll see more here.

Normally, I wouldn’t bring it up because we’re not going to use it right now. But I am mentioning it, because these new businesses are cropping up all over the place. Some are wonderful and help with the time-sink aspect of indie publishing. Others sound wonderful until you dig into their Terms of Service and realize that, like traditional publishers, these new companies are trying to make a rights grab to make their service worthwhile.

My point is this: as indie publishing becomes big business, these sorts of new things will crop up over and over again. We indies will have more opportunities, not less.

I’ve blogged about that before—about the way that my indie books (in English) are most countries around the world now, and my traditionally published books are not. Opportunities expand for indies, which is one of the coolest part of this new world in which we find ourselves.

The old world is starting to pay attention. Two statistics caught my attention this past month.

The first comes from Quartz titled “Amazon has cornered the future of Book Publishing” (as if Amazon is the only ebook service in the world), has this little nugget right after the lede:

Between 2010 and 2015, the number of ISBNs from self-published books grew by 375%. From 2014 and 2015 alone, the number grew by 21%.

Quartz cites Bowker, the company that issues ISBNs as the source of those statistics, but Quartz misses half the story. Many ebooks on Amazon (and other services) don’t use traditional ISBNs at all. Amazon doesn’t require them for Amazon-only ebook publishing. So even though the growth in ISBNs has been astronomical, that growth doesn’t begin to measure the actual number of indie ebook titles published.

Traditional publishers—after all their mergers these last ten years—have drastically scaled back the number of titles they publish. The money isn’t in traditionally published titles any more. It’s in indie, and that money has dispersed through individual authors and small publishers, rather than gathering in a few large companies.

That’s what these services are going after—they’re following the money.

Don’t believe me?

Then look at the second statistic, this one from The Guardian about Kickstarter. Kickstarter has become one of the major players in getting books published. Here’s the quote:

Of course, Kickstarter doesn’t get involved in the messy business of producing books – it’s a platform that puts people who want to produce books in touch with others all over the world who want to support their projects. But if you put the 1,973 publishing pitches that were successfully funded in 2015 together with the 994 successful comic and graphic novel projects, then last year’s tally of 2,967 literary projects puts the crowdfunding site up among publishing’s “Big Four.”

The Guardian goes on to quote Publishers Weekly statistics on one of the Big Four, Simon & Schuster. Apparently, S&S only published 2,000 titles last year. Heh. More books, more readers.

Full disclosure here. We just finished our third Kickstarter, and it was by far our most successful. If you contributed, thank you! I greatly appreciate it.

I think one of the reasons for the success is the broadening use of Kickstarter among the general population. People love to fund publishing projects on the site, and there are more people funding those projects than ever before.

I also think we know how to run a Kickstarter now, and it shows. We’ll be doing a few more as time goes on.

Kickstarter and other crowd-funding websites make starting projects—and continuing projects easier. There are also more ways to sell books, as I mentioned last week, in discussing Storybundle (and all the other bundles). Really successful Storybundle sales numbers can rival those that put books on The New York Times bestseller list in a given week. I’ve had bundles that have outperformed the ebook bestsellers on the Times list. (Of course, I have been in bundles that haven’t done as well either.)

Opportunities abound now. And everything is changing so fast that taking time away to write a blog series, like I just did, puts me far behind the curve in what’s growing and changing in the new side of the industry.

Frankly, I love the changes, and I love the growing opportunities.

This new world of publishing has not only kept my career alive, it has revived me as well. I’m now doing things I could only dream of a few years ago.

And that’s completely cool.

I’m teaching a class this week so am pressed for time. When you comment, be aware that I might not be able to put the comment through in a timely fashion. But I will put it through.

Thanks to all of you for the support through the contract series and beyond. You folks are just great!

And, as always, if this post has been valuable to you, please leave a tip on the way out.

Thanks!

Click paypal.me/kristinekathrynrusch to go to PayPal.

“Business Musings: Good Things,” copyright © 2016 by Kristine Kathryn Rusch. Image at the top of the blog copyright © 2016 by Canstock Photo/sjenner13.

Terence Bayler, R.I.P.

The prominent British actor Terence Bayler has died at the age of 86. This obit will tell you more about him, including the fact that he played The Bloody Baron in Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone.

We are interested in his work with Monty Python and in the individual works of the gents who made up Monty Python. We especially note that he thought of and delivered what I think is the funniest single line in all of the Monty Python works. I wrote about it here.

The post Terence Bayler, R.I.P. appeared first on News From ME.

What I would have said in the Europe debate at Conference

Conference, I’ve been a member of this party for over twenty years and this is the first time I’ve been moved to speak at a Federal conference. On the same day that the Fabians are telling Labour they need to turn their back on Europe and abandon support for freedom of movement, we as a party are stating clearly that we will not do that.

Conference, in the referendum the Leave side took an argument that should have been ours and twisted it.

They told the people that voting Leave would somehow take back control. And that worked because people feel they’ve lost control. They see governments – national and local – they feel they have no control over, they see massive corporations riding roughshod over people’s wishes, they see a climate spiralling out of control.

So when someone told them they could fix all this and give them back control, of course they listened. When Farage and Johnson and Gove and Stuart and all the others told them they had a remedy to cure all ills, that Brexit was the modern snake oil which could give them back control, they listened.

Conference, they listened because we weren’t talking to them about power and control. We didn’t talk about how being part of the EU made us part of the largest and most powerful economic bloc on the planet, we didn’t talk about how the EU reins in the power of business – like we’ve seen with Apple just recently – and we didn’t convince them that we needed the power of working together to tackle climate change.

As a party we need to lead the fight against Brexit in Parliament and in a future referendum. But we need to do more. Conference, we need to talk about power. We need to show how being in the EU gives us all the power to do more, and the control people are seeking wasn’t being taken away from them by the EU but by our own system here in the UK. We’ve had decade after decade of governments elected by a minority of the people in this country and then ignoring the rest of the voters. We’ve seen power stripped away from local governments, with people feeling they’ve got no say in what happens to their town with everything decided by faceless bureaucrats. But these bureaucrats aren’t in Brussels, they’re in Whitehall and voting to leave the EU will only give them more power, not less.

Conference, I support this motion because, just as I did on June 23rd, I think the best future for this country is a member of the EU. But if and when we get the chance to make that case to the country again, be it in a general election or a referendum we need to talk about power and not only how the EU can give more power to people, but how we also need to change the way the UK works so never again do people feel so powerless that they’ll listen to the snake oil promises of the Leave campaign. Only liberalism can give them back real power and real control, and we have to make that case.

Edgy humour isn't funny any more? Don't blame political correctness, bame Poe's law.

Homicide And Old Lace

As someone who's occasionally had to salvage a complete dog of a film project, I have a real affinity for the inventive rescue job, in which the producers use footage in ways they'd never intended to try to make something out of nothing. And in this case... During the few months when Brian Clemens was sacked from "The Avengers" before returning, his replacement had produced a cold mess of an episode, Terrance Dicks and Malcolm Hulke's "The Great Great Britain Crime". Contrary to fan legend, it was actually finished -- but it was 63 minutes long, it veered between painfully straight-faced bits and lame jokes, and it had massive plot-holes and characters being idiots to advance the story. Even by Avengers standards, it made no sense. Clemens salvaged the other two episodes produced while he was away, but he wanted to bury this one deep.

Fast-forward a year. They're about to be cancelled, they're behind schedule and down-to-the-wire for their last American airdates, they're way short on money, Brian Clemens is in dire need of sleep... it's time for desperate measures.

What we got is like if Gene Roddenberry, when writing "The Menagerie" around the original Star Trek pilot, first got really really drunk.

Just over half the episode (27 minutes) is the edited highlights of "The Great Great Britain Crime" -- reworked for comedy, stitched together with silent-movie music and a lurid pulp narration from Steed's boss Mother. Plus he throws in clips from other old episodes, similarly recut for comedy. There's only about two-and-a-half scenes of new material with Steed -- all the rest is a framing story, with Mother telling a story to his spy-adventure-loving maiden aunties.

But what makes this episodes something special is how dear old aunties Harriet and Georgina are *merciless* to the story -- seizing on every plot hole (why *does* Steed go along with the villains' plan?), every unbelievably idiotic authority figure ("Did he marry into an important family?"), every convenient bulletproof vest, even the villains firing a machine-gun on an ordinary London street with no one noticing -- and forcing Mother to justify them on the fly. What it is, is like sitting in on a gleefully malicious notes session with Brian Clemens as script editor, skewering everything the writer has tried to get away with. ("They had reached an impasse," intones Mother. Harriet: "What does that mean?" Georgina: "It means they'd run out of plot.")

I can only imagine what it must have been like for Dicks and Hulke to switch on the episode when it finally aired...

But to top it all off, the restitching of the old scenes is a masterclass in how you can lop out swathes of dull footage and still make the results flow. All the missing explanations are neatly covered in one new scene between Steed and Mother (who wasn't even in the original episode). In an elegant bit of plot judo, they use a blatant implausibility in the shot footage (a bomb goes off right beside the baddie and *doesn't* kill him, just blows a hole in the wall) to justify lopping out an entire redundant action sequence (the bomb actually *does* kill him and they can skip chasing him any further). And the half-scene mentioned above is where they've presumably replaced a serious action sequence with a comedy one -- in just four shots they manage to do a stylish little fight in which *every single actor* is doubled, both the long-gone guest actors and the regulars, so you never see a single face clearly. And it's seamless!

Avengers generally fans hate this one, presumably because it's Just Too Silly. But as a writer, and as an editor who knows what it's like to go to war with uncooperative footage -- there's a sort of malevolent enthusiasm to the whole thing. It manages to make the cliches look deliberately stylized, and find wit in the witless. That's a hell of a job.

If you leave your kids alone, it’s not predatory strangers who are a risk.

DINOSAUR COMICS PRESENTS: urushiall you want to know about urushiol

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about | |||

|

|||

| ← previous | September 12th, 2016 | next | |

|

September 12th, 2016: Jughead #9 is out this now! I wrote it, I get to write Jughead comics now! You can read a preview RIGHT HERE Also: HELLO! Romeo and/or Juliet is being published in the UK, and the book has a new cover there! THIS IS EXCITING – Ryan | |||

It’s Bayes All The Way Up

[Epistemic status: Very speculative. I am not a neuroscientist and apologize for any misinterpretation of the papers involved. Thanks to the people who posted these papers in r/slatestarcodex. See also Mysticism and Pattern-Matching and Bayes For Schizophrenics]

Bayes’ Theorem is an equation for calculating certain kinds of conditional probabilities. For something so obscure, it’s attracted a surprisingly wide fanbase, including doctors, environmental scientists, economists, bodybuilders, fen-dwellers, and international smugglers. Eventually the hype reached the point where there was both a Bayesian cabaret and a Bayesian choir, popular books using Bayes’ Theorem to prove both the existence and the nonexistence of God, and even Bayesian dating advice. Eventually everyone agreed to dial down their exuberance a little, and accept that Bayes’ Theorem might not literally explain absolutely everything.

So – did you know that the neurotransmitters in the brain might represent different terms in Bayes’ Theorem?

First things first: Bayes’ Theorem is a mathematical framework for integrating new evidence with prior beliefs. For example, suppose you’re sitting in your quiet suburban home and you hear something that sounds like a lion roaring. You have some prior beliefs that lions are unlikely to be near your house, so you figure that it’s probably not a lion. Probably it’s some weird machine of your neighbor’s that just happens to sound like a lion, or some kids pranking you by playing lion noises, or something. You end up believing that there’s probably no lion nearby, but you do have a slightly higher probability of there being a lion nearby than you had before you heard the roaring noise. Bayes’ Theorem is just this kind of reasoning converted to math. You can find the long version here.

This is what the brain does too: integrate new evidence with prior beliefs. Here are some examples I’ve used on this blog before:

All three of these are examples of top-down processing. Bottom-up processing is when you build perceptions into a model of the the world. Top-down processing is when you let your models of the world influence your perceptions. In the first image, you view the center letter of the the first word as an H and the second as an A, even though they’re the the same character; your model of the world tells you that THE CAT is more likely than TAE CHT. In the second image, you read “PARIS IN THE SPRINGTIME”, skimming over the duplication of the word “the”; your model of the world tells you that the phrase should probably only have one “the” in it (just as you’ve probably skimmed over it the three times I’ve duplicated “the” in this paragraph alone!). The third image might look meaningless until you realize it’s a cow’s head; once you see the cow’s head your model of the world informs your perception and it’s almost impossible to see it as anything else.

(Teh fcat taht you can siltl raed wrods wtih all the itroneir ltretrs rgraneanrd is ahonter empxlae of top-dwon pssirocneg mkinag nsioy btotom-up dtaa sanp itno pacle)

But top-down processing is much more omnipresent than even these examples would suggest. Even something as simple as looking out the window and seeing a tree requires top-down processing; it may be too dark or foggy to see the tree one hundred percent clearly, the exact pattern of light and darkness on the tree might be something you’ve never seen before – but because you know what trees are and expect them to be around, the image “snaps” into the schema “tree” and you see a tree there. As usual, this process is most obvious when it goes wrong; for example, when random patterns on a wall or ceiling “snap” into the image of a face, or when the whistling of the wind “snaps” into a voice calling your name.

Most of the things you perceive when awake are generated from very limited input – by the same machinery that generates dreams with no input

— Void Of Space (@VoidOfSpace) September 2, 2016

Corlett, Frith & Fletcher (2009) (henceforth CFF) expand on this idea and speculate on the biochemical substrates of each part of the process. They view perception as a “handshake” between top-down and bottom-up processing. Top-down models predict what we’re going to see, bottom-up models perceive the real world, then they meet in the middle and compare notes to calculate a prediction error. When the prediction error is low enough, it gets smoothed over into a consensus view of reality. When the prediction error is too high, it registers as salience/surprise, and we focus our attention on the stimulus involved to try to reconcile the models. If it turns out that bottom-up was right and top-down was wrong, then we adjust our priors (ie the models used by the top-down systems) and so learning occurs.

In their model, bottom-up sensory processing involves glutamate via the AMPA receptor, and top-down sensory processing involves glutamate via the NMDA receptor. Dopamine codes for prediction error, and seem to represent the level of certainty or the “confidence interval” of a given prediction or perception. Serotonin, acetylcholine, and the others seem to modulate these systems, where “modulate” is a generic neuroscientist weasel word. They provide a lot of neurological and radiologic evidence for these correspondences, for which I highly recommend reading the paper but which I’m not going to get into here. What I found interesting was their attempts to match this system to known pharmacological and psychological processes.

CFF discuss a couple of possible disruptions of their system. Consider increased AMPA signaling combined with decreased NMDA signaling. Bottom-up processing would become more powerful, unrestrained by top-down models. The world would seem to become “noisier”, as sensory inputs took on a life of their own and failed to snap into existing categories. In extreme cases, the “handshake” between exuberant bottom-up processes and overly timid top-down processes would fail completely, which would take the form of the sudden assignment of salience to a random stimulus.

Schizophrenics are famous for “delusions of reference”, where they think a random object or phrase is deeply important for reasons they have trouble explaining. Wikipedia gives as examples:

– A feeling that people on television or radio are talking about or talking directly to them– Believing that headlines or stories in newspapers are written especially for them

– Seeing objects or events as being set up deliberately to convey a special or particular meaning to themselves

– Thinking ‘that the slightest careless movement on the part of another person had great personal meaning…increased significance’

In CFF, these are perceptual handshake failures; even though “there’s a story about the economy in today’s newspaper” should be perfectly predictable, noisy AMPA signaling registers it as an extreme prediction failure, and it fails its perceptual handshake with overly-weak priors. Then it gets flagged as shocking and deeply important. If you’re unlucky enough to have your brain flag a random newspaper article as shocking and deeply important, maybe phenomenologically that feels like it’s a secret message for you.

And this pattern – increased AMPA signaling combined with decreased NMDA signaling – is pretty much the effect profile of the drug ketamine, and ketamine does cause a paranoid psychosis mixed with delusions of reference.

Organic psychosis like schizophrenia might involve a similar process. There’s a test called the binocular depth inversion illusion, which looks like this:

(source)

The mask in the picture is concave, ie the nose is furthest away from the camera. But most viewers interpret it as convex, with the nose closest to the camera. This makes sense in terms of Bayesian perception; we see right-side-in faces a whole lot more often than inside-out faces.

Schizophrenics (and people stoned on marijuana!) are more likely to properly identify the face as concave than everyone else. In CFF’s system, something about schizophrenia and marijuana messes with NMDA, impairs priors, and reduces the power of top-down processing. This predicts that schizophrenics and potheads would both have paranoia and delusions of reference, which seems about right.

Consider a slightly different distortion: increased AMPA signaling combined with increased NMDA signaling. You’ve still got a lot of sensory noise. But you’ve also got stronger priors to try to make sense of them. CFF argue these are the perfect conditions to create hallucinations. The increase in sensory noise means there’s a lot of data to be explained; the increased top-down pattern-matching means that the brain is very keen to fit all of it into some grand narrative. The result is vivid, convincing hallucinations of things that are totally not there at all.

LSD is mostly serotonergic, but most things that happen in the brain bottom out in glutamate eventually, and LSD bottoms out in exactly the pattern of increased AMPA and increased NMDA that we would expect to produce hallucinations. CFF don’t mention this, but I would also like to add my theory of pattern-matching based mysticism. Make the top-down prior-using NMDA system strong enough, and the entire world collapses into a single narrative, a divine grand plan in which everything makes sense and you understand all of it. This is also something I associate with LSD.

If dopamine represents a confidence interval, then increased dopaminergic signaling should mean narrowed confidence intervals and increased certainty. Perceptually, this would correspond to increased sensory acuity. More abstractly, it might increase “self-confidence” as usually described. Amphetamines, which act as dopamine agonists, do both. Amphetamine users report increased visual acuity (weirdly, they also report blurred vision sometimes; I don’t understand exactly what’s going on here). They also create an elevated mood and grandiose delusions, making users more sure of themselves and making them feel like they can do anything.

(something I remain confused about: elevated mood and grandiose delusions are also typical of bipolar mania. People on amphetamines and other dopamine agonists act pretty much exactly like manic people. Antidopaminergic drugs like olanzapine are very effective acute antimanics. But people don’t generally think of mania as primarily dopaminergic. Why not?)

CFF end their paper with a discussion of sensory deprivation. If perception is a handshake between bottom-up sense-data and top-down priors, what happens when we turn the sense-data off entirely? Psychologists note that most people go a little crazy when placed in total sensory deprivation, but that schizophrenics actually seem to do better under sense-deprivation conditions. Why?

The brain filters sense-data to adjust for ambient conditions. For example, when it’s very dark, your eyes gradually adjust until you can see by whatever light is present. When it’s perfectly silent, you can hear the proverbial pin drop. In a state of total sensory deprivation, any attempt to adjust to a threshold where you can detect the nonexistent signal is actually just going to bring you down below the point where you’re picking up noise. As with LSD, when there’s too much noise the top-down systems do their best to impose structure on it, leading to hallucinations; when they fail, you get delusions. If schizophrenics have inherently noisy perceptual systems, such that all perception comes with noise the same way a bad microphone gives off bursts of static whenever anyone tries to speak into it, then their brains will actually become less noisy as sense-data disappears.

(this might be a good time to remember that no congentally blind people ever develop schizophrenia and no one knows why)

II.

Lawson, Rees, and Friston (2014) offer a Bayesian link to autism.

(there are probably a lot of links between Bayesians and autism, but this is the only one that needs a journal article)

They argue that autism is a form of aberrant precision. That is, confidence intervals are too low; bottom-up sense-data cannot handshake with top-down models unless they’re almost-exactly the same. Since they rarely are, top-down models lose their ability to “smooth over” bottom-up information. The world is full of random noise that fails to cohere into any more general plan.

Right now I’m sitting in a room writing on a computer. A white noise machine produces white noise. A fluorescent lamp flickers overhead. My body is doing all sorts of body stuff like digesting food and pumping blood. There are a few things I need to concentrate on: this essay I’m writing, my pager if it goes off, any sorts of sudden dramatic pains in my body that might indicate a life-threatening illness. But I don’t need to worry about the feeling of my back against the back fo the chair, or the occasional flickers of the fluorescent light, or the feeling of my shirt on my skin.

A well-functioning perceptual system gates out those things I don’t need to worry about. Since my shirt always feels more or less similar on my skin, my top-down model learns to predict that feeling. When the top-down model predicts the shirt on my skin, and my bottom-up sensation reports the shirt on my skin, they handshake and agree that all is well. Even if a slight change in posture makes a different part of my shirt brush against my skin than usual, the confidence intervals are wide: it is still an instance of the class “shirt on skin”, it “snaps” into my shirt-on-skin schema, and the perceptual handshake goes off successfully, and all remains well. If something dramatic happens – for example my pager starts beeping really loudly – then my top-down model, which has thus far predicted silence – is rudely surprised by the sudden burst of noise. The perceptual handshake fails, and I am startled, upset, and instantly stop writing my essay as I try to figure out what to do next (hopefully answer my pager). The system works.

The autistic version works differently. The top-down model tries to predict the feeling of the shirt on my skin, but tiny changes in the position of the shirt change the feeling somewhat; bottom-up data does not quite match top-down prediction. In a neurotypical with wide confidence intervals, the brain would shrug off such a tiny difference, declare it good enough for government work, and (correctly) ignore it. In an autistic person, the confidence intervals are very narrow; the top-down systems expect the feeling of shirt-on-skin, but the bottom-up systems report a slightly different feeling of shirt-on-skin. These fail to snap together, the perceptual handshake fails, and the brain flags it as important; the autistic person is startled, upset, and feels like stopping what they’re doing in order to attend to it.

(in fact, I think the paper might be claiming that “attention” just means a localized narrowing of confidence intervals in a certain direction; for example, if I pay attention to the feeling of my shirt on my skin, then I can feel every little fold and micromovement. This seems like an important point with a lot of implications.)

Such handshake failures match some of the sensory symptoms of autism pretty well. Autistic people dislike environments that are (literally or metaphorically) noisy. Small sensory imperfections bother them. They literally get annoyed by scratchy clothing. They tend to seek routine, make sure everything is maximally predictable, and act as if even tiny deviations from normal are worthy of alarm.

They also stim. LRF interpret stimming as an attempt to control sensory predictive environment. If you’re moving your arms in a rhythmic motion, the overwhelming majority of sensory input from your arm is from that rhythmic motion; tiny deviations get lost in the larger signal, the same way a firefly would disappear when seen against the blaze of a searchlight. The rhythmic signal which you yourself are creating and keeping maximally rhythmic is the most predictable thing possible. Even something like head-banging serves to create extremely strong sensory data – sensory data whose production the head-banger is themselves in complete control of. If the brain is in some sense minimizing predictive error, and there’s no reasonable way to minimize prediction error because your predictive system is messed up and registering everything as a dangerous error – then sometimes you have to take things into your own hands, bang your head against a metal wall, and say “I totally predicted all that pain”.

(the paper doesn’t mention this, but it wouldn’t surprise me if weighted blankets work the same way. A bunch of weights placed on top of you will predictably stay there; if they’re heavy enough this is one of the strongest sensory signals you’re receiving and it might “raise your average” in terms of having low predictive error)

What about all the non-sensory-gating-related symptoms of autism? LRF think that autistic people dislike social interaction because it’s “the greatest uncertainty”; other people are the hardest-to-predict things we encounter. Neurotypical people are able to smooth social interaction into general categories: this person seems friendly, that person probably doesn’t like me. Autistic people get the same bottom-up data: an eye-twitch here, a weird half-smile there – but it never snaps into recognizable models; it just stays weird uninterpretable clues. So:

This provides a simple explanation for the pronounced social-communication difficulties in autism; given that other agents are arguably the most difficult things to predict. In the complex world of social interactions, the many-to-one mappings between causes and sensory input are dramatically increased and difficult to learn; especially if one cannot contextualize the prediction errors that drive that learning.

They don’t really address differences between autists and neurotypicals in terms of personality or skills. But a lot of people have come up with stories about how autistic people are better at tasks that require a lot of precision and less good at tasks that require central coherence, which seems like sort of what this theory would predict.

LRF ends by discussing biochemical bases. They agree with CFF that top-down processing is probably related to NMDA receptors, and so suspect this is damaged in autism. Transgenic mice who lack an important NMDA receptor component seem to behave kind of like autistic humans, which they take as support for their model – although obviously a lot more research is needed. They agree that acetylcholine “modulates” all of this and suggest it might be a promising pathway for future research. They agree with CFF that dopamine may represent precision/confidence, but despite their whole spiel being that precision/confidence is messed up in autism, they don’t have much to say about dopamine except that it probably modulates something, just like everything else.

III.

All of this is fascinating and elegant. But is it elegant enough?

I notice that I am confused about the relative role of NMDA and AMPA in producing hallucinations and delusions. CFF say that enhanced NMDA signaling results in hallucinations as the brain tries to add excess order to experience and “overfits” the visual data. Fine. So maybe you get a tiny bit of visual noise and think you’re seeing the Devil. But shouldn’t NMDA and top-down processing also be the system that tells you there is a high prior against the Devil being in any particular visual region?

Also, once psychotics develop a delusion, that delusion usually sticks around. It might be that a stray word in a newspaper makes someone think that the FBI is after them, but once they think the FBI is after them, they fit everything into this new paradigm – for example, they might think their psychiatrist is an FBI agent sent to poison them. This sounds a lot like a new, very strong prior! Their doctor presumably isn’t doing much that seems FBI-agent-ish, but because they’re working off a narrative of the FBI coming to get them, they fit everything, including their doctor, into that story. But if psychosis is a case of attenuated priors, why should that be?

(maybe they would answer that because psychotic people also have increased dopamine, they believe in the FBI with absolute certainty? But then how come most psychotics don’t seem to be manic – that is, why aren’t they overconfident in anything except their delusions?)

LRF discuss prediction error in terms of mild surprise and annoyance; you didn’t expect a beeping noise, the beeping noise happened, so you become startled. CFF discuss prediction error as sudden surprising salience, but then say that the attribution of salience to an odd stimulus creates a delusion of reference, a belief that it’s somehow pregnant with secret messages. These are two very different views of prediction error; an autist wearing uncomfortable clothes might be constantly focusing on their itchiness rather than on whatever she’s trying to do at the time, but she’s not going to start thinking they’re a sign from God. What’s the difference?

Finally, although they highlighted a selection of drugs that make sense within their model, others seem not to. For example, there’s some discussion of ampakines for schizophrenia. But this is the opposite of what you’d want if psychosis involved overactive AMPA signaling! I’m not saying that the ampakines for schizophrenia definitely work, but they don’t seem to make the schizophrenia noticeably worse either.

Probably this will end the same way most things in psychiatry end – hopelessly bogged down in complexity. Probably AMPA does one thing in one part of the brain, the opposite in other parts of the brain, and it’s all nonlinear and different amounts of AMPA will have totally different effects and maybe downregulate itself somewhere else.

Still, it’s neat to have at least a vague high-level overview of what might be going on.

We have a terrible electoral system, but it’s not gerrymandered

In the same way that the guest facilities of the Watergate Hotel are not much remembered, neither is the political career of Elbridge Gerry, 9th Governor of Massachusetts and 5th Vice-President of the United States. Both have managed to have their names remembered down the years by having them attached to a particular form of scandal. Thus, every account of potential political wrongdoing and cover-up finds itself with ‘-gate’ stuck on the end of it, and any complaint about changing electoral boundaries is almost certain to call it a Gerrymander. (The original ‘Gerry-mander’ was a constituency for the Massachusetts State Senate, said to resemble a salamander, and drawn in order to bolster the chances of Gerry’s supporters being elected)

‘Gerrymander’ is being thrown around a lot today as the Boundary Commission for England have announced their proposed boundaries for new constituencies in England. As these reflect new rules on the total numbers of MPs (down from 650 to 600) and the way in which constituencies are made up, there are plenty of major changes on the electoral map. Many existing constituency names disappear, others merge and mutate into new ones, and wholly new entities are formed. Compounded to this is the general and ongoing effect of population movement and change in the UK, which means that every boundary review leads to a reduction in ‘Labour constituencies’ and an increase in ‘Conservative constituencies’.

To some, all this represents a gerrymandering of constituencies. To which I say no, this is a gerrymander:

(you might need to click on it to see it in its full ridiculous detail)

That’s how the thirteen congressional districts in North Carolina are allocated. The fourth, ninth and twelfth are all classic examples of the art of gerrymandering, meandering ribbon-like constituencies with only tenuous connections between the various parts of them, but the whole state has been divided up in bizarre and unusual ways to create a certain end result. North Carolina’s not the only state that looks like that – it’s a common feature across the USA, where most states have their boundaries drawn in an explicitly political process run by the state government, not an arms-length boundary commission.

(One point worth making here is that the aim of a successful gerrymander is not to create ‘safe’ seats for the party seeking to benefit from it. If a population is divided 50-50 between Party A and Party B, 50% of the seats where party A wins 90%-10% and 50% seats where Party B wins by the same just gives us a deadlock. However, if Party A can make 75% of the seats ones it’s sure of winning 60-40, Party B can have the remaining 25% of the seats to win 80-20, but will have no chance of winning overall power, despite both parties having the same number of votes.)

The Boundary Commission works within the rules its set by the government (which are flawed) but the constituency boundaries themselves are not gerrymandered. Yes, there are some odd boundaries in there, but that’s almost always going to happen when trying to make natural communities fit within artificially imposed boundaries. The population of the country doesn’t live in a bunch of obvious communities that are all within the electoral quota needed to make a Parliamentary constituency, so boundaries are going to end up doing odd things.

The problem comes from the boundary review being part of a system that’s fundamentally broken at the national level. Claims from the Tories and Labour that the review might under or over-represent them as a result miss a fundamental point: our electoral system massively over-represents both of them. On the present – supposedly unfair to the Tories – boundaries, 37% of the vote got them 51% of the seats, while Labour got 35% of the seats in Parliament with just 30% of the votes and the SNP managed 9% of the seats on just 5% of the vote.

Complaining about gerrymandering in constituency boundaries is truly missing the wood for the trees (or the zoo for the salamander, if we’re trying to keep our metaphors straight). Why bother gerrymandering individual seats, when you’ve already got a system that’s massively biased in favour of you? If you want to reform the process, you need to remember that odd constituency boundaries and reviews like this are a necessary feature of our electoral system, not a bug. If you want a system that truly represents people, don’t get distracted complaining about non-existent gerrymanders, work instead to get us a better electoral system.

Fifteen Years Ago

We all have our stories on where we were the morning of 9/11/01 when we heard. I don't think I've ever told mine here but it was no more remarkable than yours and maybe less.

I had my phone ringer off and my voicemail poised to answer any calls while I slept. I woke up, staggered to the bathroom and then noticed the number of waiting calls on my answering machine. I think it was something like 14 and I instantly thought, "Something has happened." It could have been very good or very bad, but when I played back the first message, I knew instantly it was in the "very bad" category.

It was from my friend Tracy and she was near hysterics, crying and moaning about "those poor people in New York." But she didn't say what it was that had happened to those poor people in New York. I listened to other messages and got a snatch here and a snatch there of what it was, then I rushed into my office, turned the TV on to CNN and sat there for hours with, I'm sure, the "Springtime for Hitler" look on my face. I was sitting right where I'm sitting now to write this.

I think I started watching about 8:30 AM Pacific Time. That was 11:30 in New York. By that time, the twin towers of the World Trade Center had each been hit. Each had burned for a time. Each had finally collapsed. The Pentagon had been hit. All air travel in the United States had been halted. New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani had ordered evacuations and other emergency efforts. (Whatever happened to that fine, brave man of that morning?)

Most of the shockers were over by the time we West Coasters joined the trembling audience but we didn't know that. We were still wondering: What can happen next? Is there another plane somewhere? Is there more to this? When the unthinkable happens, you brace yourself for more unthinkable things.

I flashed back, as most of us of a certain age have to with moments of tragedy, to 11/22/63 and the news that John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. Immediately upon hearing, we were all desperate to know: What can happen next? Will someone now assassinate the Vice-President? Is there more to this?

On both days, what had already happened was horrifying enough. But part of the horror was that sense of suddenly being in another world where that kind of thing happened…and you had no idea if or when something else like it would follow. On both days, it took a while to accept that maybe we were back to where most things made some sort of sense.

I'm thinking about that today and also about what would happen if a tragedy of that magnitude occurred today. I think we'd still have that feeling of being lost and helpless for a time. I'd like to think we'd have at least some of that feeling of togetherness and of being one country indivisible, with partisan differences set aside. But I don't think it would last very long.

I think the President of the United States would be impeached, and for many people that would be a higher priority than tending to the dead bodies and living victims. Even if that President had snapped into action, rather than sit in a classroom and read to children…even if that President hadn't ignored certain warning signs, I think we'd immediately have hearings like the ones on Benghazi, only bigger and more of them with real, not manufactured outrage. Four Americans died in the Benghazi attack. When Americans and others were killed by attacks on U.S. eembassies during the administration of George W. Bush, no one cared. No hearings were held. No one was blamed.

I'm not saying that was right or wrong; just that that's how it was.

3000 Americans died in the 9/11 attack and perhaps another thousand have died indirectly because of that day. So instead of seven investigations like we've had over Benghazi, we'd have 7,000 over an attack the size of 9/11…and yes, I know the math is ridiculous. I'm just trying to suggest scale here. Another tragedy the size of 9/11 or even a tenth the size would be a lot worse than Benghazi, right?

I don't think 9/11 brought our country to our current level of partisanship. We were well on our way to it back when they impeached Bill Clinton.

So now we have the situation where no matter who gets elected in November, 40-49% of the country will be livid and will be hating our new president and predicting the imminent destruction of the United States of America. Some will even in a way be hoping for it so they can say "See?" to those who voted "the wrong way."